A graph query language is a programming language designed to retrieve and manipulate data stored in a graph database. The rise in popularity of these databases—across applications in knowledge graphs, biology, and the semantic web—comes from the simple fact that much of the world’s data is naturally interconnected. This means that a lot of data is naturally represented as a graph, where nodes represent entities and edges encode relationships between the entities.

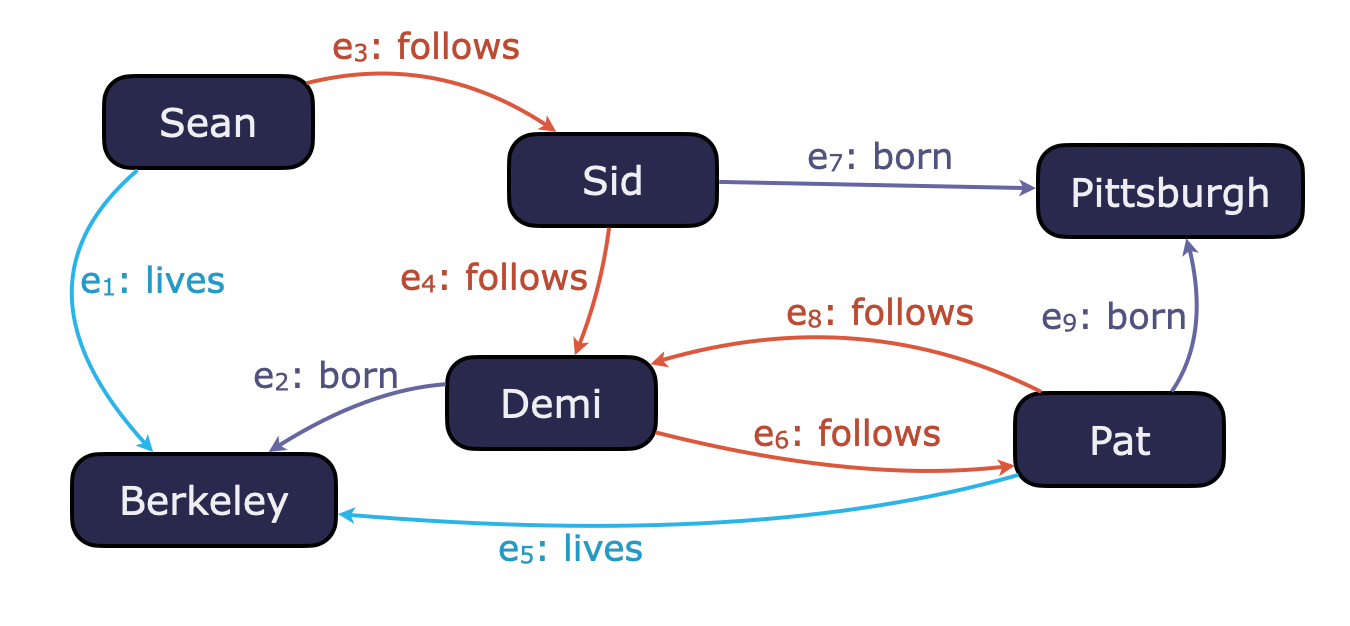

Think of, for example, a social network that encodes who follows who on a social media platform, where these people were born, and where they currently live. Traditional relational query languages, which think of this data as tables, are not designed to make it easy to query connections in the data. Graph query languages care about such connections right from the start. They see the data as nodes representing entities (people and cities) and edges encoding relationships (who follows who, who was born where, and who lives where).

A graph database with node identifiers: Sean, Sid, Demi, Pat, Berkeley, Pittsburgh; edge identifiers: e1, e2,..., e9; and edge labels: follows, born, lives.

A major difference between current graph languages and traditional relational languages is that the former make it easy to return flexible-length paths, which is useful in scenarios where you want to trace connections, such as journalists mapping relationships in investigative journalism or analysts tracking funds in fraud investigations. This is a lot harder in some traditional relational languages, where the user must specify multiple joins explicitly and potentially recurse over these.

The complexity in graph databases is in finding graph patterns, i.e., a graph-structured query is matched against the graph database. One of the most fundamental patterns is a path query. A path query is a query of the form P = x →* y. Here, x and y are variables, and query P extracts all pairs of nodes such that there is a path in the graph database between them. More generally, a regular path query (RPQ) P = x →⍺ y specifies that the relationship on the path match the regular expression ⍺. Restricting ⍺ to be a regular expression enables path concatenation, union, and other nice operations.

Example: Measuring Influence. We can use RPQs to determine influence within a network. If we define influence by the chain of followers, we can write the query (Sid, follows+, ?x). This starts at Sid and outputs all nodes reachable by one or more follows edges.

In this scenario, Sean is the most influential because his reach extends to the largest network.

Many applications require knowledge of the full path, not just its endpoints. You don't just want to know that Sid influences Pat, you want to know how (e.g., Sid → Demi → Pat). Or in a much larger social network, perhaps you want to know what the shortest friend–path from you to Kevin Bacon is (instead of just knowing the distance, which is on average at most 6 under the small-world assumption).

This introduces a massive computational bottleneck. Without restrictions, the number of paths in a highly connected graph can be infinite due to cycles (loops). To manage this, modern standards like GQL and SQL/PGQ define path modes, which are restrictions that ensure the length and number of paths returned is finite. Some example path modes include

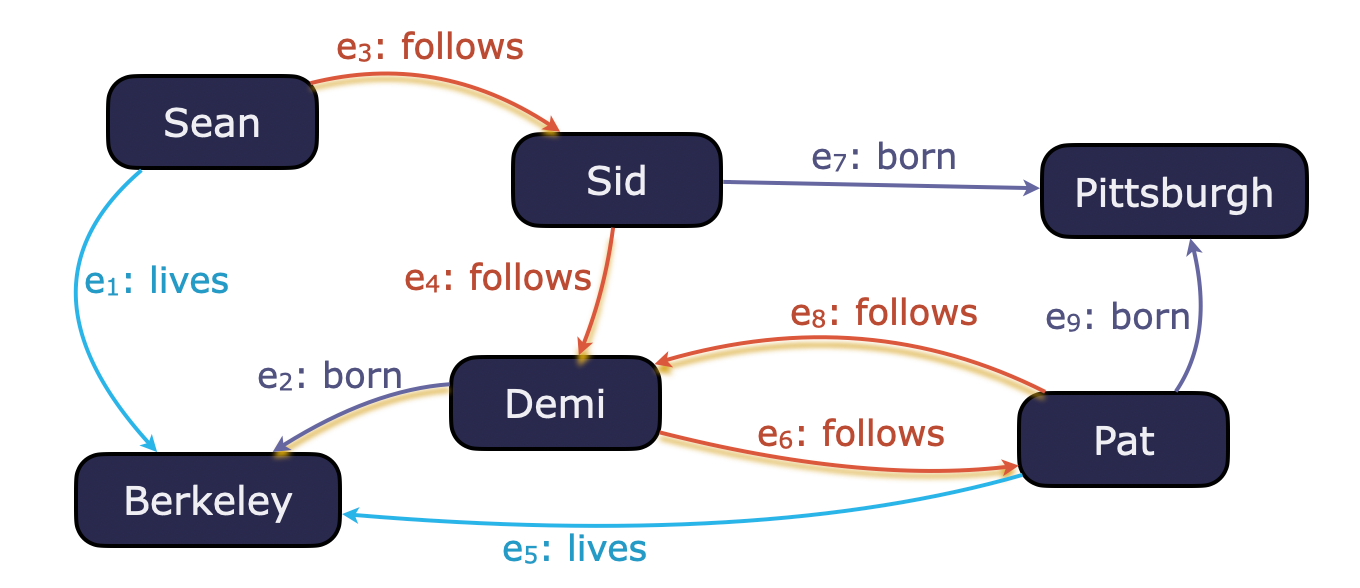

Example: Measuring Influence. Suppose we want to find where the people in Sean’s network live. We use the RPQ (Sean, follows+ · born, ?x), which outputs all people reachable from Sean by any number of follows edges plus a born edge, with the path mode SIMPLE. Valid paths are

Without the path mode SIMPLE, an infinite number of paths satisfy the RPQ because of the cycle formed by the edges between Demi and Pat. For example, the path highlighted in the picture below would not be returned under the restriction of the SIMPLE path mode because this path repeats node Demi.

Despite the importance of these features, before 2024 no database engine supported all regular expressions in RPQs, and no engine fully supported RPQs with all of the path modes provided by GQL and SQL/PGQ. A key difficulty in this goal is that in highly connected graphs, there can be millions or billions of paths between two nodes, so a system needs to deal with these paths without ever enumerating them.

PathFinder is a unified framework designed to fill the gaps left by prior systems. It is the first engine capable of returning paths for all regular path queries and all path modes standard in GQL and SQL/PGQ.

One of the main technical innovations of Pathfinder is that it uses a compact data structure, based on path multiset representations, that can store paths efficiently. This compact representation relies on the product graph of a query expression and a graph database, which is basically the cross product of the graph and the automaton for the regular expression. Crucially, PathFinder only constructs the subgraph of the product graph that is needed to answer the query.

Another advantage of Pathfinder is that it can return paths in a pipelined fashion (one by one), meaning that an algorithm can be paused once a path is found. If a user only needs the top 10 paths, the system can pause immediately after finding them, rather than waiting for all billion paths to be computed.

PathFinder proves that you do not need to choose between expressiveness (asking complex questions) and performance (getting fast answers). It offers a blueprint for the next generation of graph databases to fully implement the rich features promised by the GQL and SQL/PGQ standards without suffering from scalability issues.

***

Explore the research behind PathFinder by RAI-affiliated researchers Marcelo Arenas, Leonid Libkin, Wim Martens, Domagoj Vrgoč, and their coauthors Vicente Calisto, Benjamín Farías, and Carlos Rojas.