In math research, one of the hardest challenges isn’t solving problems—it’s finding good ones in the first place. While generating unproven conjectures is easy, generating meaningful ones is not. At one extreme, a conjecture may be trivial or technically uninteresting. At the other, it may lie beyond the scope of our existing techniques and systems, rendering it basically impossible.

So, how do you choose a problem that is interesting, yet tractable? Striking this balance requires experience, intuition, and a kind of mathematical taste.

You can ask the same thing about finding patterns in data. It’s easy to say something obvious about your data, but how do you extract insights that are nontrivial, actionable, and predictive about the future?

Automated conjecturing is the branch of AI and mathematics focused on designing systems that generate new mathematical conjectures (without proving them). The field dates back to the 1950s, with one of the earliest systems being Douglas Lenat’s Automated Mathematician (AM). AM used heuristic rules to propose conjectures in set theory and number theory. These early systems were ambitious and influential, even though they often produced large numbers of uninteresting statements. They demonstrated, for the first time, that machines could generate mathematical discoveries rather than simply verify them.

In the late 80s, Siemion Fajtlowicz developed the program Graffiti, which generated thousands of conjectures, at least 60 of which were later proven by mathematicians. Graffiti relied on the Dalmatian heuristic, which proposes a conjecture only when:

By enforcing these requirements, the Dalmatian heuristic keeps the number of proposed statements manageable, while ensuring that the statements it produces are worthwhile.

TxGraffiti is an automated conjecturing system built for graph theory, developed by Randy Davila (RAI, Rice University). It focuses on generating linear inequalities relating pairs of graph invariants—such as the independence number, domination number, and zero-forcing number—using a large database of graphs.

Given two graph invariants P and Q and a database of graphs, the program finds numbers m and b so that the inequality P(G)≤m*Q(G)+b holds over all graphs G in the database. These constants can be found by solving a linear program.

The number of inequalities generated might be huge, and post-processing is necessary to determine a small output of interesting inequalities. One tool to do this is a conjecture’s touch, which is the number of times a conjecture’s inequality actually holds with equality over the graphs in the database. High-touch conjectures tend to be stronger and more interesting.

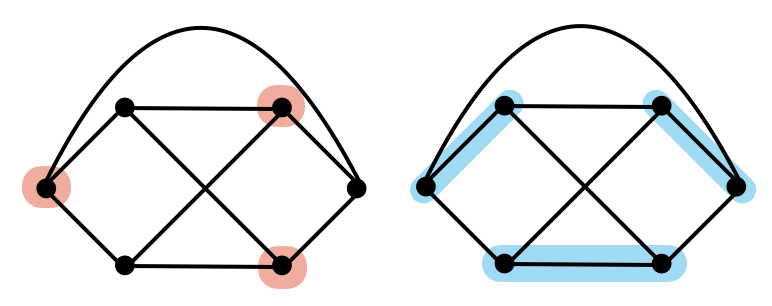

Surprisingly, the touch heuristic alone has been remarkably effective. For example, TxGraffiti produced the following conjecture later proven by Caro, Davila, and Pepper (see the picture below).

For G an r-regular graph, α(G) ≤ μ(G).

Orange nodes on the left form a maximum independent set, blue edges on the right form a maximum matching.

The independence number of G, α(G), is the size of the largest set of nodes that doesn’t contain any edges.

The matching number, μ(G), is the size of the largest set of edges where no two edges share a node.

The latest version of TxGraffiti can also implement Fajtlowicz’s Dalmation heuristic, merging classic ideas with modern methods. Several other conjectures from TxGraffiti have also been proven (e.g., these papers 1, 2, 3).

From the 1980s until the early 2000s, conjecturing systems were developed in parallel with automated theorem provers (ATPs) and proof assistants such as HOL, Coq (now Rocq), Isabelle, and Lean. These systems matured rapidly and now handle increasingly sophisticated mathematics.

But automated conjecturing remained less popular until recently, when interest surged following a high-profile study by DeepMind. Fascinatingly, traditional symbolic or heuristic approaches still outperform deep neural networks at conjecturing, perhaps because “surprise” and “mathematical novelty” are hard to quantify for ML models.

Although TxGraffiti works with graph invariants, its core ideas generalize to any tabular dataset. Hypothetically, techniques from automated conjecturing could uncover hidden patterns, expose surprising relationships, highlight structure, or suggest hypotheses worth testing in data. Imagine if the techniques from automated conjecturing were part of the decision intelligence toolbox, and could help identify emerging trends, inform predictions, or sharpen models.

Automated conjecturing hints at a future where machines don’t just solve problems—they help us discover which problems matter.